|

| Photo credit: express.co.uk |

As so often was the case when he graced the football pitches in Spain and the rest of Europe, leave it to former Barcelona midfield maestro

Xavi Hernández to

hit the nail on the head about José Mourinho: "He was the assistant coach, someone who understood the philosophy of Barça and who shared many of the same characteristics of Van Gaal. He was very respected by the players. He trained us sometimes alone at Barça B and he was excellent. I'm surprised that he became known for another type of football, more defensive, because he wasn't like that with us."

And therein lies probably one of the most fascinating aspects of The Special One's trajectory thus far.

Much has been said and written about Chelsea's misfortunes this season. But the truth is that, in fact, this downward spiral was not that hard to envision - that is, if you pay some attention to more than just the immediate results. What was once a coach with a great eye for detail and tactical innovation (albeit a more subtle one) has become a shadow of his former self, relying exclusively on his dressing room management skills - à la

Luiz Felipe Scolari.

Mourinho was given his first chance at a marauding Benfica and he immediately transformed the team, at every single level. However, the fact that he didn't stay there for more than a couple of months didn't help us understand just what he was capable of.

He needed to get to União de Leiria, by then an average mid-table club in the Portuguese top tier, to really make his mark. By December 2001, his team were already flying as high as third, two spots ahead of his eventual employers FC Porto, who rushed to sign him before anyone else would. But what impressed a few (including this column, admittedly) the most was not necessarily the table standings, but rather how he had got there, with proactive football, unafraid of anyone and eschewing altogether the tenets of the typically reactive football played in Portugal in the early seasons of the century. He was a breath of fresh air. The players loved to play for him. Some of them shone like they had never done before (and some of them never would again).

Despite some revisionism laid out by a few football writers as of late, both União de Leiria and FC Porto played much more than just controlled, run-of-the-mill football under a very inspirational coach, like some would have you believe. Mourinho paid excruciating attention to detail (as the

famous leaked report by then-opposition scout André Villas-Boas) in an attempt to always get the upper hand on his opponents.

He was indeed inspirational for other coaches, as he seemed to bring a fresh new approach to football and its coaching. Even though he didn't preach anything revolutionary, he seemed to be one of the few who represented the entire package - not only was he able to preach possession-based football and training sessions where the ball was ever present, he also had a penchant for press conferences and soundbites, a supreme confidence in his skills and the air of someone who was going places, all rolled into one.

|

| Photo credit: telegraph.co.uk |

What impressed this column the most was however the fact that his approach seemed to be based on a philosophical approach. Interviewed and queried for books and PhD thesis, he was able to show the reasoning behind his decisions on the pitch and in the dressing room. Despite winning the Portuguese league, the Portuguese Cup and the then UEFA Cup in his first full season at FC Porto, Mourinho knew he couldn't just rest on his laurels and went in search of something to motivate his players and keep them in check - hence the intense work on the 4x4x2 diamond that was a relative rarity back then and that proved so successful in Europe, yielding the Champions League in 2004.

Mourinho always had the collective, the group in the back of his mind. In

one of the best books written about his career and approach, the Portuguese coach explained how zonal marking was the only option to defend set pieces, since it held the whole team responsible for the play's outcome - once again the group before the individuals. He went on to talk about the principle of complexity (how the relations between the different individuals in a team changed the team dramatically and how any coach should pay attention to it).

On

another book, he talked about the Guided Discovery, i.e. how the coach had the responsibility to lay clues for the players to find out the best answer to a specific problem was, Mourinho himself knowing all along what he wanted the answer to be. He bragged about how he wanted to dominate matches or at least control them, if domination was not an option. He talked about how he wanted his teams to press high and then rest with the ball. Players were delighted with his innovative sessions. In short, he sounded much more like the coach Xavi had got to know at Barça.

Everyone knows how the story goes by now. After winning the Champions League, Chelsea's new owner wanted Mourinho to lead his team and wouldn't take no for an answer. The Portuguese was an instant success, from his very first press conference. He won his players over in a heartbeat and indeed, in the first matches of the off-season, it was already possible to see many of the movements that Mourinho had implemented at FC Porto.

|

| Photo credit: bleacherreport.net |

According to this column, that Chelsea side was probably vintage Mourinho, the place and time where he sublimated all his skills and honed his qualities even further. He was clearly enjoying himself and everyone (opponents included, sometimes) was basking in his presence. That was the time where his side steamrollered the opposition, sometimes shutting up shop at 1-0, sometimes running rampant. Players like Damien Duff, Arjen Robben, Frank Lampard, Didier Drogba, Eidur Gudjohnsen, Paulo Ferreira and so many others enjoyed some of the best moments of their playing careers in what seemed to be an almost unstoppable Chelsea. All of the main tenets were there and it seemed Mourinho was the alchemist that had come across the definitive winning formula.

- 3. Always Brightest Before The Night

Mourinho decided to go to Inter Milan as the luminary that would set the oft-floundering

Massimo Moratti's club on their way back to glory. And that Mourinho did. But that was also where you could sense things starting to fall apart a little bit, a very hard proposition to sustenance when everyone knows Inter ended up winning the Italian League and the Champions League in the two seasons that the Portuguese coach spent in Italy.

|

| Photo credit: telegraph.co.uk |

However, there seemed to be more than just the adaptation to a new country, culture and club (all the best coaches do it, just look at what

Pep Guardiola has done at Bayern Munich since joining in 2013). The focus on keeping the ball was much less present. The single holding midfielder started giving way to a more solid

doble pivote, man-marking started to be interspersed with zonal marking at set pieces, the team were more dependent on individual players. Some of the football was admittedly poor, while some was clearly

scintillating. Inter might have deservedly won the Champions League, but, to some followers of his career, Mourinho seemed to be missing a step or two. The fact that he won the Champions League based on a more reactive brand of football might have been a strong reason for what has been happening since.

|

| Photo credit: dailytelegraph.com.au |

It is hard to qualify José Mourinho's time at Real Madrid. Some will call it a success, while others would have a harder time doing it. Even Mourinho himself labelled the 2012/13 season the worst of his career, at the end of a very tough, politically-ridden 3-year cycle at Real Madrid. In this case, the most important aspect is not the loads of silverware he piled up or that should have grabbed for his club, but rather how things unravelled from a tactical point of view. While the

5-0 defeat against Barça five years ago almost to the day was clearly one of the toughest days in his professional life, things should not be based solely on that particular result, especially because he managed to do so much more while he was at the helm.

On the contrary, this is about how he got to those results - often times with a much more reactive brand of football, resorting to have his team play exclusively to the strengths of Cristiano Ronaldo, even when it had costly implications on the rest of the squad and their playing style. It seemed Mourinho was involving, going back on all the principles that had brought him such a high level of success.

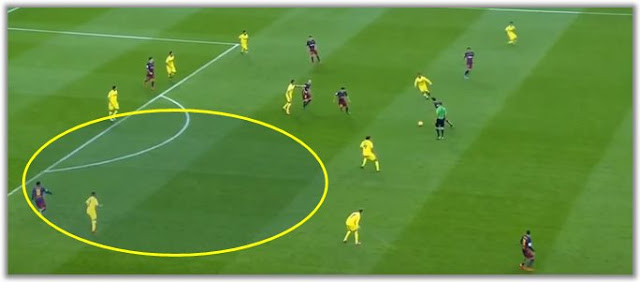

Man-marking at set pieces became the norm everywhere. Transitions became the team's livelihood. Ceding initiative to opponents soon became the traditional way for Mourinho's side to have the upper hand. Sérgio Ramos or Pepe (neither of whom excel in the build-up phase of play) as the team's holding midfielder was not an unusual sight and denounced the team's focus. Controlling matches with frustrating underhand tactics was not uncommon either. A man so steeped in his principles of positive football and collective thinking seemed to have sold his soul in exchange for more and more trophies.

It is hard to fathom matches that are more made in heaven than Mourinho and the United Kingdom. Each party delivers what the other one wants, craves, loves and hates - in equal parts. And because Mourinho came back with a vengeance amidst claims of being The Happy One, it was even harder to get the point across that this was a different Mourinho, more interested in managing things from his tower and less willing to impose his football on his adversaries.

|

| Photo credit: backpost.com |

While the spirit in which he surrounds his team might have been enough to get past a befuddled Manchester City, a David Moyes-led United and the typical Arsène Wenger's Arsenal, all the signs were there: Chelsea were not playing top-class football, either offensively or defensively. Man-marking was now spread to open play, which left the team (and particularly John Terry) much more exposed to anyone who was able to envision the blind spots. The ball was now clearly something to give away (the

elimination at the hands of 10-man Paris Saint-Germain at Stamford Bridge being the ultimate example) and ideas to attack opponents' goals seemed to be limited to "give the ball quickly to

Hazard" and "Let's see if

Fàbregas is capable of pulling a through-ball".

Clearly Chelsea will bounce back from this stupor and will probably progress from the group stage at the hands of FC Porto themselves. The 7 defeats were clearly a statistical blip. But blaming all of that on a thin squad or the typical 10-year cycles of successful managers seems to be a lazy exercise of reasoning, of a certain blindness to what had been taking shape beforehand. It remains to be seen just how far José Mourinho can take this squad and how he will be able to mend some of the fractures that already started to appear in the dressing room.

This piece is no way destined to draw attention on all of José Mourinho's falls, but rather how his path has been a slippery slope and how there has been some evidence that such a blip might not be too far off. The siege mentality that the Portuguese usually implements on the clubs he manages tend to work, but it's a scorched earth approach that often leaves many of its members burnt - particularly at a time where player power is at its height and it's increasingly difficult to confine footballers in a "one for all and all for one" mentality for too long.

It is this column's opinion, however, that unless Mourinho reverts his recent trajectory in terms of pure footballing approach, the titles that seemed to be coming his way so thick and fast will tend to spread out eventually, maybe sooner rather than later, as he fails to innovate and make his football as dominating as the approach Mourinho himself adopts at press conferences, where he is still "

el puto amo". If he does not step up his game, players will soon catch up with it and start losing faith in his skills and it will be increasingly hard to see his players

weep over his departure.